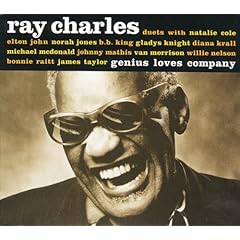

- Here We Go Again (with Norah Jones)

- Sweet Potato Pie (with James Taylor)

- You Don’t Know Me (with Diana Krall)

- Sorry Seems To Be The Hardest Word (with Elton John)

- Fever (with Natalie Cole)

- Do I Ever Cross your Mind? (with Bonnie Raitt)

- It Was A Very Good Year (with Willie Nelson)*

- Hey Girl (with Michael McDonald)

- Sinner’s Prayer (with B.B. King)

- Heaven Help Us All (with Gladys Knight)

- Over The Rainbow (with Johnny Mathis)

- Crazy Love (with Van Morrison)

- Unchain My Heart (with Take 6)

- Mary Ann (with Poncho Sanchez)

It won a basketful of Grammy Awards: Heaven Help Us All with Gladys Knight, won Best Gospel Performance. Here We Go Again with Norah Jones won Best Pop Vocal Collaboration and Record Of The Year. The album was voted Best Pop Vocal Album and Album Of The Year. One Grammy went to arranger Victor Vanacore for his arrangement on Over The Rainbow. The album went multi-platinum and hit #1 on the album charts in several countries.

Co-stars & Personnel:

B.B. King, Willie Nelson* - vocals, guitar; Bonnie Raitt - vocals, slide guitar; Norah Jones - vocals, piano; Michael McDonald - vocals, keyboards; Diana Krall, Elton John, James Taylor , Johnny Mathis, Van Morrison, Natalie Cole, Gladys Knight - vocals; Danny Jacob, George Marinelli, Jeff Mironov, Michael Landau, Michael Thompson, George Doering, Charles Fearing, Irv Kramer - guitar; Randy Waldman - piano, keyboards; Alan Pasqua - piano; Billy Preston - Hammond b-3 organ; Michael Bearden - keyboards; David Hayes, Abraham Laboriel, Sr., Trey Henry, Tom Fowler - bass guitar; James Gadson, Jim Keltner, Ray Brinker, Shawn Pelton - drums; Bashiri Johnson - percussion. Clarence McDonald arranged and played keyboards on Heaven Help Us All. For an unabridged personnel listing see Wikipedia.

Slash claimed playing the original guitar parts on Sorry Seems To Be The Hardest Word, but "[...] after Ray died, the executive producer used a friend of his instead and took my part off, even though Ray thought I was more bluesy".

Concord 2248-2, 2004-08.

See these interesting pages for documentary information on some of the sessions.

The AP Archives have an interview with Gladys Knight (from 2005), and some making of-footage from the recording of Heaven Help Us All (from 2004).

Part 1 Making of:

Part 2 Making of:

This article from October 2004 in Mix by Blair Jackson presented an evocative making-of story:

Producer John Burk explained, "[...] One of our main goals was to try to put him in the room live with the guest artists — the way he used to make records. He makes magic in the studio. And as I learned from working with him, perhaps his greatest gift is his ability to really communicate what a song is about and the emotion behind it. And when he works with another artist, he draws that out of them, as well."Another article on MSNBC Today also revealed some important information on the genesis of the album, and Ray's last productive months (full story here):

"[...] For the past 40 years, Charles mostly recorded at his RPM Studios [...] and the bulk of Genius Loves Company was cut there, using some of Charles' regular musicians and his longtime engineer, Terry Howard. Burk produced most of the album, but five tracks were helmed by Phil Ramone, who used Ed Thacker as his engineer. The three songs that were cut live with a full orchestra on the Warner Bros. L.A. scoring stage were co-produced by Howard and engineered by Bobby Fernandez. SACD pioneer Herb Waltl also earned a co-production credit for his assistance on the project, and it was he and Howard who facilitated Burk's initial meeting with Charles. The album was mixed by Al Schmitt at Capitol's Studio C on a Neve VR.

Burk notes that having Ramone onboard for the project was particularly important. “Phil is clearly one of the greatest producers and engineers ever. He's also a friend and I consider him a mentor,” he says. “When I first talked to Ray about doing the project in his own studio, which has such a distinctive vibe and so much history, I wanted to bring Phil in right away because there's nobody better at making a room work. We ordered some baffling and did various other things to make the room sound better — Phil even brought in a huge garden umbrella to put over the drums because they were leaking all over the room. He put that in and taped in some foam and that really helped.”

“It's a very bright room,” Ramone comments, “but I still didn't want to use a lot of isolation. It's decent-sized, maybe 40-by-30. It has a sort of late-'50s, early-'60s feeling, which is, of course, when he made some of his greatest music. Ray is very fussy about what he wants to hear, but he's also very cooperative and was open to suggestions.”

It was Ramone who chose the vocal mic that Charles and his partners used. “We tried a couple of things at the outset,” he says. “We started with some Neumanns, but for some reason, they didn't feel right to me so we ended up using Audio-Technica 4060s. Once we settled on that, we stuck with it. I like to get things early; I'm a first-taker. I don't want to be changing mics on take five — if we get there — especially on someone like Ray Charles.” Ramone's vocal chain on Charles also included a Summit EQ and a Neve 1073 preamp. “I like to go with the simplistic best,” Ramone comments. “I like API and Avalon [preamps], too. I'm good with any of the top-of-the-line Class-A amps.” The project was recorded to Pro Tools, and Ramone notes that he used RPM's Quad 8 Virtuoso console mostly just for monitoring.

Once Charles, the producers and the duet partners agreed on song choices, the work turned to picking appropriate arrangements. “It was so many different styles, you wanted to treat them differently,” Burk says. “There was a core band, which was pretty much Ray's guys — bass player Tom Fowler is probably the main one there — and then for drums, Ray wanted Ray Brinker, who has worked with [jazz singer] Tierney Sutton and others, and Randy Waldman did a lot of the piano work. Billy Preston was on the B3, and then there was a whole variety of guitar players.”

As for the vocal arrangements, Ramone says, “Where I could prepare [the duet partners], I'd send them an idea of the arrangement, which would usually give a sense of where they might come in. But you learn your lesson fast with Ray, because he's such a great arranger himself and he's full of ideas and he always seems to have an opinion about how things should go. So you might come into a session thinking it's going to go one way, but with Ray, there's always the possibility that he's going to change it once you're in the room with him. If you're a singer and he feels you're stretching or straining and he doesn't like it, he'll change it. Or if he wants you to strain a little, you'll do it. He's so intuitive about how it should go.”

“He has a very clear vision of what he wants,” Burk adds, “so a big part of the [producer's] job is to get that for him. A lot of the work is the dialog you have with him before the date. Then when you get into it, there's a lot of give and take, but now and then, it's going to go a certain way and that's all there is to it.

“You don't tell Ray Charles how to sing,” he continues. “There were certain times where he'd say, ‘That's it. That's the take.’ Sometimes I'd ask him to try something and he'd say, ‘Okay.’ Other times, he'd say, ‘No.’ He knew when he got what he wanted, and he didn't do a lot of takes. Every now and then, he'd come back later and swap in a word or a line, but in general, that didn't work as well as the vocals he did in the moment with the other artists.”

As is frequently the case with these sorts of all-star projects, scheduling turned out to be one of the biggest challenges; at the beginning, Charles' demanding agenda proved to be daunting. “He was still touring in June [2003], and he'd say, ‘I have three days — the eighth, the 14th and the 29th’ — so we'd scramble to see which artists we could come up with who were free,” Burk says. “When he stopped touring, he came into the office every day and the album became his main focus, so that actually made our job a little easier.”

The first studio session, with B.B. King, came together in July 2003. “I could tell his hip was bothering him,” Burk says, “but he was an incredibly strong guy. [...] His attitude was, ‘I'm fine. I've got a little somethin' I'm dealing with. Don't worry about it. Let's go to work.’ So he might have an off-day. But he was a man of his word and a man of commitment. There was a day when he came to a session and he really wasn't feeling well, and I told him, ‘Ray, please don't ever do that again. I'm more than happy to reschedule.’ But his feeling was, ‘I said I was going to be there,’ so he showed up. He always showed up on time, ready to work.”

For engineer Howard, who had worked with Charles for nearly two decades, he could tell that his boss was not well, “and I know B.B. was kind of shocked by how weak Ray seemed. But that session was one of my most memorable, because when you hear Ray singing, you really hear the pain in his voice, but when you hear B.B. coming in, you hear the strong shoulder of a friend that someone like Ray could lean against. Ray was already frail: When he talked, he sounded like an old person. But the fire in his soul was still there and once the song started, that frail voice left him and Ray Charles the star entered the building. He belted it out and we did it in just a couple or three takes.” [...]

Another of Howard's favorites was the session with Bonnie Raitt, who Charles admired “for taking the time to really work on the song with Ray, changing a part a little here, changing the bridge this way. It was amazing to see two of the most talented people in the world crafting a song before your eyes. I know Ray really loved that track.” [...]

Originally, Burk says, he had not planned on including orchestral tracks on the album, “but Ray had an idea about a song that he wanted to do with Willie Nelson [It Was A Very Good Year] with a full orchestra. And this is something Ray would do from time to time. He said, ‘I've already got the arrangement written and I've got to tell you, it's going to be awesome.’ He was so convicted, I said, ‘Okay, let's do it!’ before I heard the arrangement. The arranger, Victor Vanacore, does these amazing detailed demos of his charts, and when I heard it, I was knocked out, too.” One thing led to another, and soon Michael McDonald and Johnny Mathis were also cutting live with the orchestra at the Eastwood Scoring Stage, which is equipped with an SSL 9000J console. [...]

By the late winter of 2004, Charles' health had declined precipitously and finding moments when he could work on the project became difficult. The knock-out duet with Elton John on John's “Sorry Seems to Be the Hardest Word,” cut last April, turned out to be the project's final recording.

“I must admit, I was a little shocked at how frail he seemed when we got together in March,” Ramone says. “Compared to the way he was the previous fall, he seemed very, very fragile. He whispered to me at one point, ‘I'm really not well.’ I wanted to cry right there. People who were around were weeping in the control room, it was so emotional. But, of course, you always hope and believe that someone will get better, and I think we all believed that he would get better. I'll say this about him: He funneled every bit of energy he had into that performance. The chemistry between Ray and Elton was just incredible.”

Though historically Charles was deeply involved in the mixing of his albums, his failing health kept him away from Schmitt's mixing sessions for the most part, and, as Burk notes, “At a certain point, he was not leaving his place much, so we set up an edNET system that would tap him into the studio so we could play the mixes for him. Even then there were times when he couldn't really give it his all. Once I got a CD ref to him, though, he played it nonstop in his car and I know he was happy with how it came out.”

Charles succumbed to liver cancer on June 11, shortly after the album was mastered. “At the time, he wasn't really admitting to any of us how ill he was,” Burk says. “But you look back at some of the songs he chose and you start to wonder: ‘Was he trying to say something?’ ‘Was he trying to make some final statements?’ I think maybe he was.”

[...] “He seemed to be reminiscing a bit. I remember [Ray] said ‘If we had known we were going to live this long, we would have taken better care of ourselves,”’ [B.B.] King told The Associated Press during a recent interview. “I told him ‘You bet.”’The late Terry Howard, Ray Charles' longtime engineer, was heavily involved in producing this album (although he wasn't fully credited for that role). In an interesting interview he revealed:

It was the last time they would talk - or perform - together. [...]

“Some of the songs I have been playing for years. Some were all-time favorites of mine that I’d never recorded. Others were songs by artists that I really liked,” Charles said before his death.

[...T]he most emotional moment came between Charles and Elton John as the two recorded John’s Sorry Seems To Be The Hardest Word. It was the last song recorded for the album and the last one Charles ever sang, Burk said.

“There wasn’t a dry eye in the recording booth,” Burk said. “It’s a very sad song, and there was just this emotion in the air.”

[...] During the recording of the album, Charles’ health was deteriorating rapidly after undergoing hip surgery and being diagnosed with a failing liver.

“He didn’t really say anything to anybody about it. He didn’t complain,” Burk said. “It never really became an obstacle.”

In fact, during the recording sessions, Charles maintained his legendary focus. Known for demanding excellence, he held to that standard during the making of “Genius Loves Company.”

“His professionalism and his attention and focus were amazing,” Raitt said. “I just think he was on it. That’s what musicians call it, being on it.”

King, who broke down while singing at Charles funeral, said he hopes the album will cross generations and genres. [...] “You know, he’s one of a kind, doing what he did and how he did it,” he said. “Ray started before some of these kids were born. I hope they will take the memory of a great guy that has done so much great work.”

"[The Grammys] were for the Genius Loves Company that I worked on. I can talk a little bit about that because that was the last year of Ray's life. We had already signed a contract and everything was progressing to do this record. And one day when we did the B.B. King song Sinner's Prayer, Ray came off the road into the studio very sick. In all my years of working with Ray, I'd never seen him even with a cold. I knew before the doctors said; when you are close with somebody, you can tell that something is wrong. I knew at the time (although I was hoping it wasn't going to be) that this might be Ray's last record. Everybody involved decided that it was instrumental that we keep Ray's spirits up and keep this record going.

It took a lot of energy for me, because after that, starting in about August, I was with Ray on a daily basis. Normally I would work with Ray about three or four days out of the week, three to six hours a day. At that point I was with him from the time he got to the studio at about eleven in the morning to the time he left at about six at night. He would be taking care of his health, and I would be in the control room going through songs and putting rough mixes together so I could play parts to him. Ray would choose a song and I would go sit down with him, and we would decide what arranger to use and what musicians to use. Ray and I would go over the song and decide what key the song would sound best in. This is something I would learn from Ray. There are two things that are very important things to do in a song. You don't set the key, because that is the key that the person can sing in. Each key has a different sound. If you go up and transpose, you'll notice that one key might sound more melodic than another one and one might sound sadder. He would say, 'Now which one sounds right for this song?' We would pick a step or two in either direction of the key the accompanying artist was singing in.

Ray taught me that tempo is very important. Sometimes we would sit there for an hour and then come in the next day and rethink it again and sit there with the metronome and count it off and play a part of the song and he would try out some vocal phrasing, and we would try different things till we felt that the emotion Ray wanted was coming through the music. Sometimes we would argue with people at the label who wanted the tempo speeded up, and you don't change Ray's decision on tempo - that's the emotion of the song."

A limited edition of this CD (Concord/Liberty/EMI 7243 8 75873 0 4) contains documentary footage of recording sessions (probably identical to the clips above), the Session Projects interview with Ray Charles from 1985, and an announcement of the film Ray.

A limited edition of this CD (Concord/Liberty/EMI 7243 8 75873 0 4) contains documentary footage of recording sessions (probably identical to the clips above), the Session Projects interview with Ray Charles from 1985, and an announcement of the film Ray.In the UK record company EMI produced a promotional CD containing interviews with 5 of Ray's duet partners - Bonnie Raitt, Elton John, Michael McDonald, Norah Jones and Willie Nelson - recounting their experience of Charles; be it working with him or their discovery of his music.

* The press release also promised a download voucher for two bonus tracks, but it's not clear if these are the known extra tracks that are part of all variants (including the 2004 pack), or if they are entirely new 'give aways'.

Promo 2014 release (short):

Promo 2014 release (longer):

AP footage:

* Mid March 2004 Willie Nelson postponed one of his concerts to make it to the recording session with Ray: "Willie has changed to Friday the 26th at 8:00p.m. He has an emergency recording with Ray Charles as Ray is not long for the world according to the production people that just called us."

See clip here.

No comments :

Post a Comment